Staying ahead of Myanmar sanctions: The 48 vessels no one is looking at

What’s inside?

On February 1st, Myanmar’s military seized power in a coup d’état. Following the military coup, the United States, EU, UK, and Canada announced targeted economic sanctions against the country’s military leaders and a handful of military-held companies. And the list of targets is bound to grow.

In this developing situation, behavioral vessel risk intelligence is critical both for:

- Companies shipping to or from Myanmar

- Financial institutions engaged in trade finance

As regulators are increasingly targeting the region, there is a lot at stake.

This blog will discuss how Windward’s maritime AI platform can help you react in real-time and avoid exposure to sanctions.

Lessons from Venezuela and what it means for Myanmar

History has shown us that sanctions and the subsequent actions of regulators can rapidly change with global events and politics. Venezuela is a classic example. After years of criminal activity and human rights abuses – OFAC ultimately imposed sanctions. But what if you had the insights to act before sanctions hit?

As sanctions continue to target more entities in Myanmar, the situation could begin to look like OFAC’s Venezuela-related sanctions. Following the introduction of sanctions on state-owned entities, including Petróleos de Venezuela, S.A. (PdVSA), OFAC designated numerous shipping companies and vessels to Specially Designated Nationals And Blocked Persons List (SDN) lists. In line with this, there may be incentives for Myanmar to conceal shipments and continue to profit from it. And Myanmar has been no stranger to high-risk behaviors in the past. For example, even before the coup, Myanmar engaged in narcotics trafficking, North Korean trade, and human rights abuses.

Proponents of harsher sanctions are pushing OFAC to designate Myanma Oil and Gas Enterprise (MOGE), one of the country’s major exporters, in hopes of cutting off military revenues. Nevertheless, Myanmar-related sanctions are currently “list-based”. So many commercial activities in the country are untouched, including, for the most part, the shipping sector. However, companies operating in high-risk sectors should not wait until regulations come.

The potential Myanmar exposure

Given the current situation, stakeholders need to be aware of their exposure to potential sanctions. For example, if you are financing trade, it’s important to know which vessels worldwide are owned by Myanmar companies.

But for comprehensive due diligence, organizations need predictive insights. This is where real-time monitoring of vessel activity and information is crucial. According to Windward Intelligence insights, roughly a dozen vessels visited Myanmar ports after the February coup for the first time. Newly arrived vessels with unusual histories and links to dubious players are important red flags. Our platform also identified that of the more than 132 vessels that loitered in Myanmar territorial waters, only half were with a Myanmar flag. Of those 64 vessels, 48, or 75%, were headed to Malaysia, Bangladesh, and Singapore, potentially with cargo.

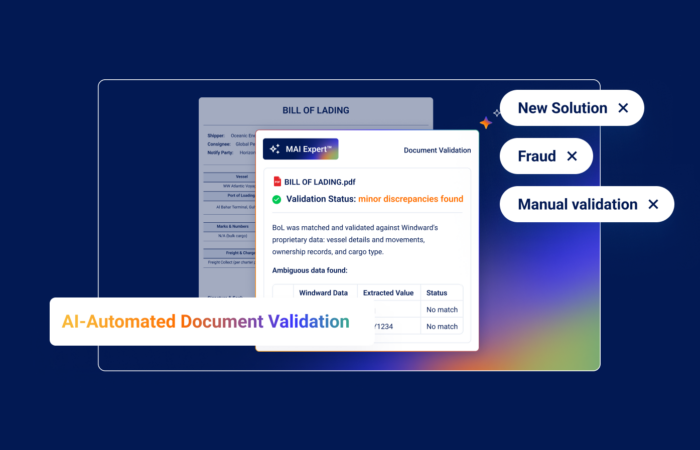

While many types of business involving Myanmar are perfectly legal, the potential for sanction evasion and illicit activity is increasing due to recent political events. With our platform, stakeholders can add or remove regimes as global sanction lists evolve, create customized risk profiles, and adjust each risk factor according to their unique needs. Companies can then control each indicator they believe may affect business decisions.

The cost of unmanaged exposure

Without the right data, a lot can go wrong. Companies doing business in Myanmar can risk involvement with individuals or entities on the OFAC SDN List or other applicable sanctions list, including any entities owned or controlled by them. What happens if a company confirms a match against one of these lists? Preventive steps, policies, and processes implemented to mitigate are all part of responsible accountability for sanctions violations. If two parties violate sanctions, in the same way, we can expect differing fines and punitive measures based on the comprehensiveness of their compliance programs. Mismanaging compliance can not only result in regulatory fines, but adverse media can hurt future sales and lead counter-parties to block your business.

For instance, in January 2020, OFAC announced a $1,125,000 settlement with a US-headquartered Marshall Islands ship management company. According to OFAC, the company chartered a vessel to a Singapore-owned company transporting sand from Myanmar to Singapore. The company provided documents stating the exported sand came from a Myanmar company on OFAC’s SDN List. It then provided alternative documents that showed a non-sanctioned exporter. Under pressure from Myanmar port officials, the US-headquartered management company accepted the revised documents and permitted the vessel to carry the goods. According to OFAC, the company managed multiple voyages with the knowledge of the company’s status. Altering trade documentation is not an acceptable compliance measure – stakeholders need to detect early warning signs and minimize the fallout.

A multi-layered approach to compliance

So what can organizations do to be one step ahead? As a basic starting point, companies trading with Myanmar should scan their transactions for the names of individuals or entities on the SDN list or other applicable sanctions lists. But it’s not as simple as that. Sanctions can also apply to entities that are owned or controlled by a sanctioned person. OFAC’s “50 Percent Rule” states that blocking sanctions apply to any legal entity owned 50% or more by a person on the SDN List.

This means companies don’t only need to screen, but accurately detect the potential risk exposure of beneficial owners and related parties of the vessel. This is no small feat. Stakeholders need to account for any number of dynamic data points in real-time.

Tell-tale signs of potentially illicit shipments include gaps in automatic identification system (AIS) data, frequent vessel name or ownership changes, and ship-to-ship transfers with other suspect vessels. Without a robust technological partner, it would be difficult to identify the anomalies and predict vessel risk. With the right tools in place, stakeholders can make data-driven decisions that best suit their risk appetite.