Whitepaper

Red Sea Crisis’ Long-Term Ramifications

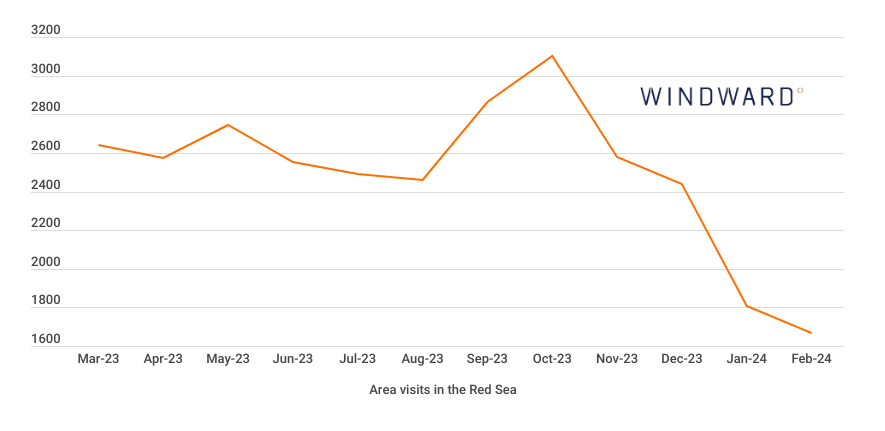

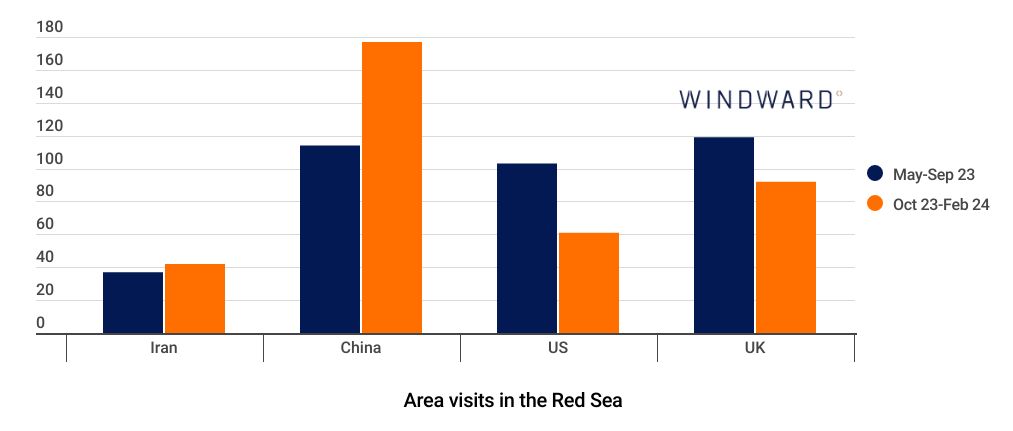

Further examination of the data reveals interesting insights into whose access is hindered. Area visits by Chinese and Iranian-flagged cargo vessels and tankers increased in October 2023-February 2024 by 55% and 13.5%, respectively (compared to May-September 2023).

By contrast, area visits by U.S.-flagged cargo vessels and tankers dropped by 41% and UK-flagged vessels experienced a 23% drop.

There are two likely reasons for the increase in Chinese voyages:

- The Houthis declared they would not attack Chinese vessels.

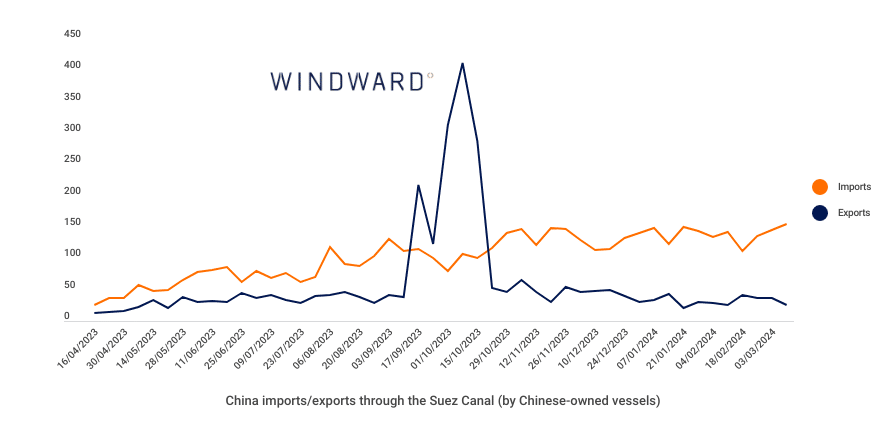

- The Chinese Ministry of Commerce and the Chinese People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) are assisting all Chinese-owned vessels in the Red Sea with the PLAN Task Force to the Gulf of Aden (currently the 45th Task Force). Overall, Chinese trade has not been affected to the same extent as that of the West.

The overall trends confirm the political alliances that have clearly formed. The Houthi disruptions and retaliatory attacks from the U.S. and UK are further dividing “the East” – China, Iran, and Russia – from “the West” – the U.S., Europe, and select Asian and Middle Eastern countries – even further.

The ability to maintain the stable flow of goods, in particular food and energy, is a key factor of national resilience. The inability to do so could lead to domestic volatility and destabilization. This knowledge will likely necessitate or motivate governments to reevaluate how to best maintain and protect their trade capabilities, which could have far-reaching consequences for geopolitical dynamics and allegiances.

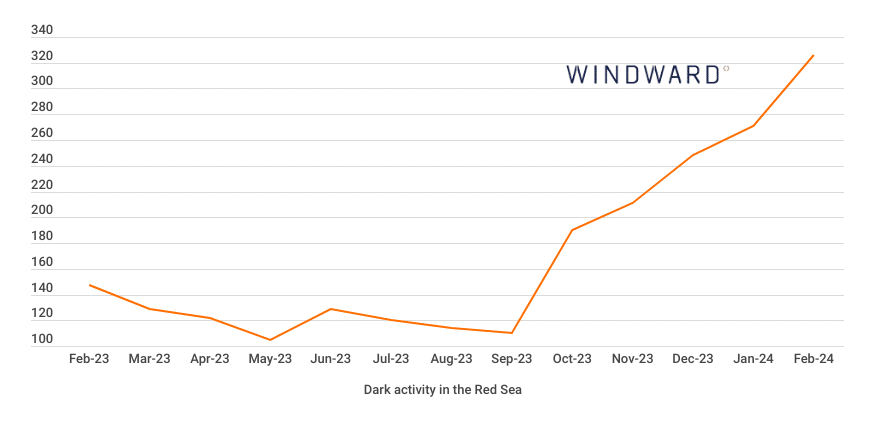

Dark activity has traditionally been a marker of illicit behavior. While it is becoming less indicative due to the rise in other, more sophisticated DSPs, it has been one of the most common and basic ways to generate leads for possible illicit activities…until the Houthis flipped the script.

Another trend spotted by the Windward platform is an increase in area visits by high- or moderate-risk Iranian-flagged cargo vessels and tankers in the Red Sea area from October 2023 to February 2024. There were 152 area visits by high or moderate-risk Iranian vessels in January-February 2024 alone, compared to a total of 191 in all of 2023 – most marked for smuggling risk.

Overall, the turmoil in the Red Sea has made law-abiding vessels more likely to adopt traditionally suspicious behaviors, making it more difficult to detect actual illicit activity and increasing the likelihood of false positives. It has also emboldened Iran to send its vessels – many notorious for smuggling and other illegal activities – through the area, despite the increased international attention and scrutiny.