The curious case of the SU RI BONG

What’s inside?

Every year, the UN Security Council Panel of Experts on North Korea publishes an update on the DPRK, the impact of sanctions and the increasingly sophisticated ways Pyongyang evades them. The most remarkable case we’ve ever encountered – involving almost every deceptive shipping practice in the book – is that of the SU RI BONG.

The curious case of the SU RI BONG begins on June 25, 2019 (though at that point in time it went by the name: FU XING 12). Flying the flag of China, the bulk carrier is dispatched to Ningbo, a Chinese shipyard, waiting to be scrapped. Except that’s not what happened.

On August 2, the FU XING 12 suddenly comes back to life. It resumes transmission, changes its name to PU ZHOU and its flag to Sierra Leone. But rather than transmit its own identifier, it takes on the MMSI of a Sierra Leone-flagged ship called the KINTEKI MARU.

The Incredible Journey

After a week drifting off the coast of China, our bulk carrier reports an empty draft and sets sail. It’s heading east.

Five days later – on August 14 – the PU ZHOU goes dark and heads towards North Korea. Perhaps by accident, the vessel resumes transmissions as it enters the DPRK’s Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ). About a week later, it goes dark again. For 47 days. During that time, the vessel’s ownership is transferred to a British Virgin Islands company – a one-ship company with no specific address or connection with any other firm.

Becoming the SU RI BONG

Roll on to October 5, and our vessel resumes transmission inside the North Korean port of Nampo. It changes its ID again, this time to the North Korean-flagged SU RI BONG. It heads up-river, and calls at the port of Songnim. Satellite images, provided by Planet Labs, indicate the bulker’s compartments are open, ready to be loaded with sanctioned DPRK coal.

A few days later, the SU RI BONG heads south. It leaves North Korea’s EEZ, and changes its identity yet again – this time, to the China-flagged HUA HAI. Repeating the trick we outlined above, it again coopts the MMSI of another vessel – the SU TONG HAI. It does so for three very good reasons: first, it bears a striking resemblance to our bulk carrier, both in size and appearance; second, it has an almost identical voyage history with the HUA HAI’S earlier incarnation; and finally, the SU TONG HAI hadn’t transmitted since January 2018, meaning there was no other vessel transmitting the SU RI BONG’s new MMSI, potentially reducing suspicion.

Fully Loaded

It’s now November 12. Sailing south, the HUA HAI reports a draft that suggests it’s fully-loaded (you’ll recall above that before docking at Songnim in North Korea its reported draft was empty). All of a sudden, it conducts U-turn for no apparent reason. Its new destination? Unknown.

Deviating from its course, our bulk carrier doesn’t call at a port. Instead, it stops off at a tiny, uninhabited, Chinese island. Satellite images show its compartments open, and what appear to be other, smaller bulk carriers, milling around it. Even more interesting is that our bulk carrier has cranes on board. They would have allowed it to self-discharge, i.e. carry out ship-to-ship transfers with the smaller vessels.

Reporting a draft change that now shows the vessel to be empty, our bulk carrier heads back towards North Korea. On November 29, it enters the North Korean EEZ, changes its identity back to SU RI BONG, and heads to the port of Nampo. It hasn’t been seen since.

Epilogue

Up until recently, all a vessel had to do to go off the grid was change its flag. Yet as the case of the SU RI BONG shows, sanctions evasion tactics have come a long way since then.

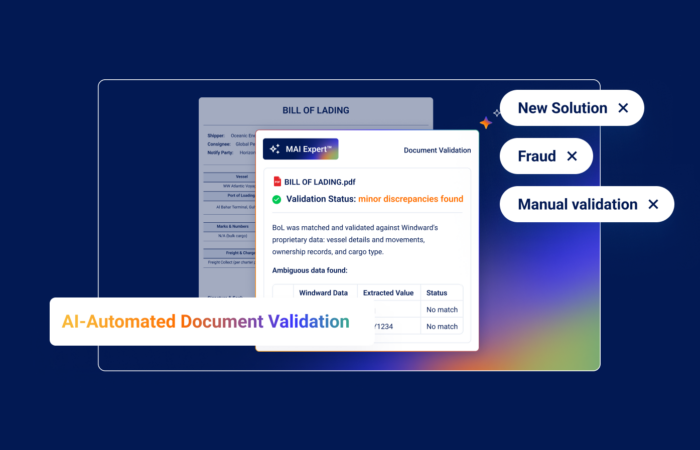

The result: traditional screening tools and list-based approaches are no longer fit for purpose, and can’t cope with these kinds of deceptions.

Staying safe in the face of these sophisticated tactics requires a new breed of behavioral-based analytics. In this way, we can see through these ever-evolving deceptive shipping practices, and discover the true behavior of vessels like the SU RI BONG.

Dror Salzman is a Customer Success Manager at Windward

If you would like additional insights or discuss any aspect of the Windward data in the UN report, please contact us: media@wnwd.com