On sanctions and oil spills

What’s inside?

Another day another attempt to circumvent sanctions – this time with ship-to-ship deceptive shipping practices

An Indonesian vessel recently picked up two tankers, the MT Freya and the MT Horse, in the middle of a ship-to-ship transfer. The reason? A likely attempt to pass Iranian oil to an unnamed customer in Asia.

Events like this are becoming increasingly common as the global maritime trade becomes increasingly complex due to a rise in regulations and limitations such as Nordstream2, Cuba, Iran, and even China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC). As a result, global organizations are trading with even more hesitation.

This particular case concerns a sanctioned vessel, the MT Horse; because of its presence on sanction lists for a while, most organizations would not even consider trading with it. The company is owned and operated by the National Iranian Tanker company and operates under the Iranian flag – it doesn’t get any more ‘red-flag’ than that.

But the case also concerns another vessel: the Panamanian flagged VLCC, owned by “Freya LTD.” As opposed to the MT Horse, this vessel is not on sanction lists, and as a result, many organizations might consider trading with them; and that would be problematic at best.

The U.S. and UK recently introduced a new regulatory framework for sanctions compliance – “deceptive shipping practices,” broadening the definition of risky behavior.

The maritime community has become accustomed to seeing vessels perform a “dark activity” where they intentionally turn off transmissions, particularly in the Arabian Gulf, or when engaging ship-to-ship in known hubs such as Basrah or Fujairah. Both activities are clearly defined as deceptive shipping practices and should, by default, raise suspicions.

This shift in the way deceptive practices are carried out make sanction evasions a complex cat and mouse game, continually evolving in sophistication and urgency.

Beyond the sea

What happens at sea does not always stay at sea.

In September, just four months before engaging with the MT Horse, the MT Freya changed its flag registration from the Marshall Islands to Panama, and soon after, ownership was changed. The Freya LTD, now the VLCC tanker’s brand-new owner, had a fleet composed of one vessel: the MT Freya.

Interestingly enough, when diving into the information of the new Freya LTD, it was revealed to share an address and telephone number with the Shanghai Future Ship Mgmt Co, who was incidentally the new commercial manager of the MT Freya.

Going back to the commercial manager reveals that, unlike the Freya LTD, the commercial manager had another vessel under its management: The Merope. The Merope is a crude oil tanker sailing under a Liberian flag, further complicating the matter of determining if the MT Freya engaged in deceptive shipping practices before the MT Horse incident.

When examining the two tankers’ behavioral trends, it is revealed that they have been operating the same routes – from Northern China to Singapore – for quite some time. The Merope, however, has also been conducting “dark activities” for over a year.

And so, the question arises: could additional dark ship-to-ship transfers have been taking place before the MT Freya even appeared at the scene?

When sanctions spill

The rise of dark ship-to-ship transfers raises another concern: the environmental risk such interactions entail.

When bad actors perform deceptive shipping practices under the radar, the implications often go beyond sanctions and compliance.

According to Reuters, during the MT Freya and MT Horse ship-to-ship transfer, an oil spill took place, bringing to light a whole new layer of risk that such engagements create.

Bad actors seem to disregard safety with the same ease they disregard compliance. As a result, those who trade with sanctioned vessels, or vessels that engage in dark activity and other deceptive shipping practices, increase the collateral damage they potentially cause.

It should be noted that according to most IGP&I clauses, such events will not be covered under their P&I policies, exposing all players involved to significant financial implications (some oil spill claims have been valued at billions of USD).

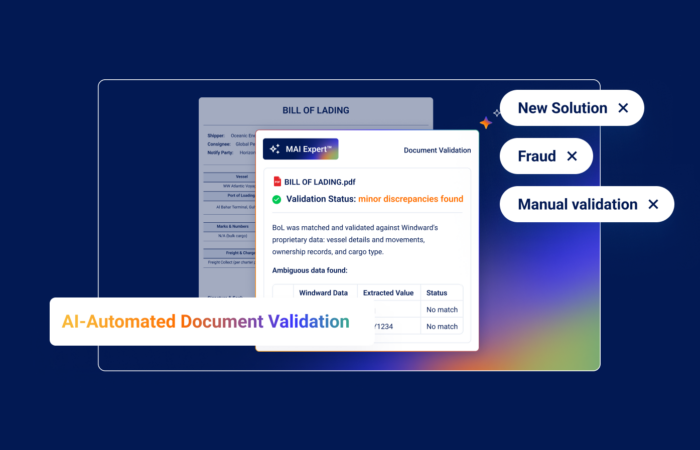

However, in today’s complex maritime environment, freight and trading desks are asked to make decisions in minutes, not hours, such complex structures and deep screening cannot be done. As a result, companies are left with a tough choice: trade fast and risk a sanctions breach event, or worse, an oil spill, or conduct a full-length screening process and potentially lose deals due to the time it takes to approve them.

A national risk

From a national perspective, deceptive shipping practices such as the MT Freya exhibited also have significant national implications.

Countries, specifically their port and coastal authorities, are expected to monitor AIS compliance and police their waters.

This is becoming a high stakes game, with state actors drawn violently into the geopolitical discussion due to sanctions circumvention or environmental events in their waters. Such occurrences led to local turmoil following the Mauritius oil spill and in other places where sanction violations took place in territorial waters.

Leaving the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) unmonitored or monitored using old-school solutions that do not provide tangible decision points and alerts leaves an opening for bad actors.

From a flag registry perspective, this case yet again highlights that although some flags have taken a proactive approach in monitoring their fleet, their hands are practically tied without proper AI tools at their disposal. Flag registries are expected to take responsibility for their fleet, an impossible task using old methods and platforms that simply fall consistently behind in this evolving scene.

It’s time to take a different approach

Global changes and security advisories, such as those implemented by OFAC and OFSI, raise the bar of standards and extend the umbrella of responsibility to the private sector. As a result, private businesses and organizations will have to increase the level of scrutiny on their counterparties, ensuring that none of the parties they engage with violate sanctions or engage with sanction violators.

The new advisories, coupled with compliance standards and new sanctions regimes such as those placed on Cuba, China, Russia, Iran, and more, have made it increasingly complicated to trade with confidence.

The answer for many has been to buy more data and spend more money on human resources, hoping the result will be a clear picture of every trade. However, the growing amount of information, the lack of clarity raw data creates, and the maritime industry’s complexity makes that a near-impossible task.

However, there are those who take a different approach; instead of collecting data, they seek insight; instead of trying to paint a picture with missing parts, they try to gain clarity from knowledge; instead of hoping they only trade with legitimate vessels, they adopt a preemptive approach to risk and know instantly and with precision just how risky each vessel they engage with is.

The energy companies, traders, banks, and other maritime professionals that use artificial intelligence (AI) have all of that information and more, enabling them to trade with confidence and always stay ahead of competitors and bad actors.

Because in 2021, when you get a gift horse, you need to look him in the mouth – and for that, you need AI.