Whitepaper

Illuminating IUU Fishing

Executive Summary

This white paper features Windward’s proprietary, artificial intelligence (AI)-driven data and behavioral insights to help you better understand the world of illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing. The aim is for you to reach higher levels of awareness and preparedness, and to assist your organization in protecting your nation’s EEZ, intersecting jurisdictions, and international waters (where applicable) from illicit activities and environmental crimes.

Windward has provided satellite imagery, fused data points, and graphs in this document to explain who is likely to engage in IUU fishing, the areas most likely to be affected, the methods used to engage in and mask IUU fishing, and the significant economic impact.

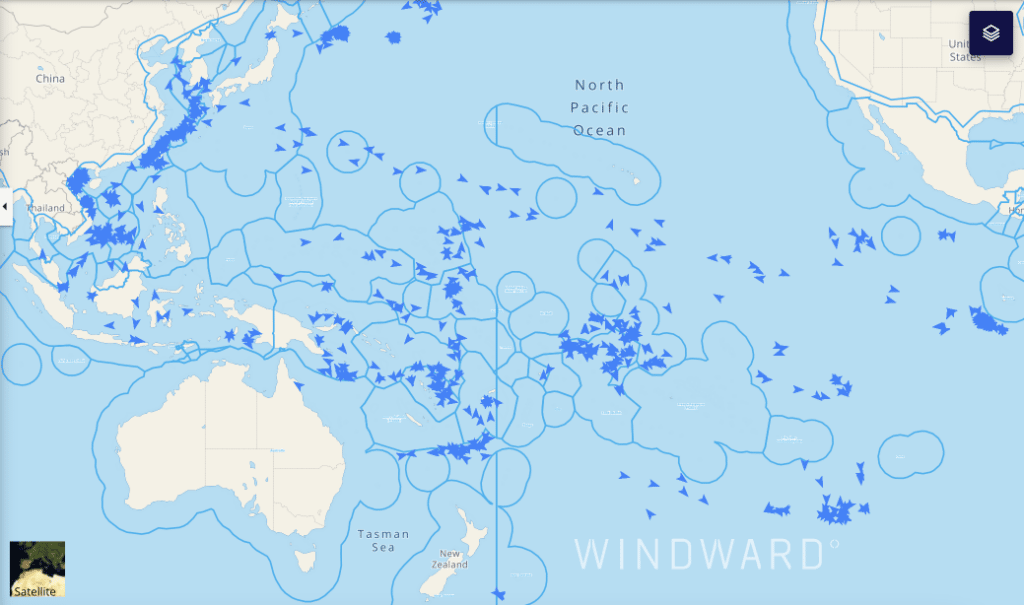

Our analysis includes general global data and insights, as well as a recurring focus on the Pacific Ocean, to show the scale and effect of IUU fishing on a specific area. Looking at a random day in April, 2022, for instance, we identified more than 2,000 Chinese fishing vessels that conducted fishing operations in the Pacific Ocean, outside of China’s EEZ.

Windward’s Maritime AITM technology was leveraged to discover and quantify IUU fishing “hot zones” and it has uncovered the traditionally unexamined and critical role of supporting fleets. This white paper also identifies hubs that support these fleets and vessels, and includes a brief example of IUU’s economic impact on a specific country.

Quantifying the Damage of IUU

“IUU fishing has replaced piracy as the leading global maritime security threat. If IUU fishing continues unchecked, we can expect deterioration of fragile coastal States and increased tension among foreign-fishing Nations, threatening geo-political stability around the world.” – United States Coast Guard in 2020

Approximately 11-19% of reported global fisheries production results from illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing and it leads to losses of roughly $10-23.5 billion in value, according to the World Wide Fund (WWF) for Nature. The EU IUU Fishing Coalition states that almost 30% of the world’s fisheries are overexploited and over 60% are already fully exploited.

This is just one aspect of the problem. The International Maritime Organization does a good job of framing how IUU fishing goes beyond the significant ecological damage it causes:

IUU fishing possesses a “potent ability to undermine national and regional efforts to conserve and manage fish stocks and, as a consequence, inhibits progress towards achieving the goals of long-term sustainability and responsibility. IUU fishing takes advantage of corruption and exploits weak management regimes…IUU fishing threatens marine biodiversity, livelihoods, exacerbates poverty, and augments food insecurity. The focus of the international community remains on IUU fishing as a serious issue for the global fishing sector that impacts negatively on safety, on environmental issues, on conservation and on sustainability.”

IUU vessels and their crews are often used to advance a great power competition between leading countries, and for criminal activities – such as forced labor, smuggling, pollution, and establishing a permanent presence despite the seasonal limitations – and both IUU and other threatening behaviors were addressed in the Quad’s statement delivered in May 2022.

To showcase the scale of such IUU fishing fleets on an average day, we zoomed in on the Pacific Ocean – an area known for its vast fishing activities. Windward identified more than 2,000 Chinese fishing vessels that conducted fishing operations in the Pacific Ocean, outside of China’s EEZ, on April 3, 2022 .

After cross-referencing WCPFC records, IATTC and SPRFMO’s databases, we found that the vessels listed there represent only 75% of the total number of Chinese fishing vessels that operate in the Pacific at any given time. This suggests that at least 25% of Chinese vessels in the Pacific are likely operating without a permit. This is just one fishing area…how many more such areas exist?

Identifying IUU Support Hubs

Where do these long distance fishing fleets go when operations at hot zones are complete?

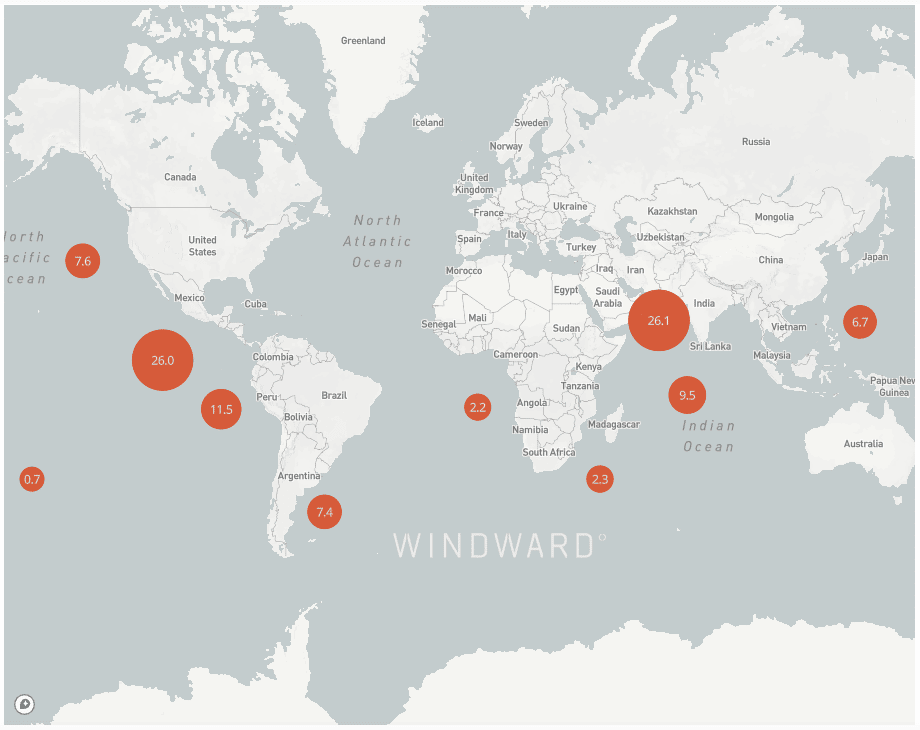

Windward’s Maritime AITM technology has identified support hubs in the vicinity of the fishing hot zones that are used to optimize these operations. For example, when not meeting at sea, 41.5% of fishing fleets that were likely involved in IUU incidents sailed to China/Taiwan, 10.7% sailed to Mauritius, and 3.4% sailed to Uruguay.

Both Mauritius and Uruguay are suspected of acting as hubs to support China’s long-distance fishing fleets, together with,Peru and Fiji. These hubs are critical for accomplishing the geopolitical aims of the countries mostly responsible for IUU fishing. Without the hubs, geographical and seasonal constraints would seriously limit the staying power of the bad actors.

Chinese vessels are proliferating year-round, regardless of season, and presumably using these hubs for power projection and expansion, highlighting the geopolitical impact of IUU fishing. If this continues unabated, or accelerates, it could upset the fragile international order.

Writing in Forbes, Jill Goldenziel warns of a potentially dark future: “China’s illicit fishing is sowing the seeds of geopolitical strife around the globe. Its incursions into other countries’ EEZs, and its theft of livelihoods, GDP, and protein could easily spark conflict. Its use of fishing vessels for lawfare and power projection endangers the environment and human lives. If China’s IUU Fishing continues unchecked, fragile coastal states will deteriorate from environmental damage, leading to further instability.”

Governments must go beyond merely looking at IUU fishing and start investigating the security risks posed by IUU fishing operations.

The image below shows the trade flows between IUU hot zones and the supporting hubs the fleets connect to:

Of the +2,000 vessels actively fishing in the Pacific, 50% were involved in STS operations in the open sea, including the aforementioned vessels not conducting port calls in the past year. Meaning 50% of fishing vessels get the supplies they need and discharge their catch without ever having to call port, or formally report on their activities. Approximately 60% of recorded meetings were with reefers and the rest (40%) involved oil bunkering vessels. The first are mainly used to get the catch back to land, while the latter keep them fueled while at sea.

The majority of the vessels that have been identified by Windward as supporting vessels fly under the flags of Panama, a flag of convenience, and China. As mentioned above, a whopping 75% of fishing vessels likely to engage in IUU fishing are flying either the Chinese or Taiwanese flags. But only 38.4% of supporting fleet vessels are flying under those same flags – how do we account for the discrepancy?

Three possible explanations based on reasonable assumptions:

- It would be quite easy for Chinese-owned vessels to sail under the Panamanian flag – they could even do so via online registration.

- The catch from these fishing operations does not always go back to China and a non-Chinese flag allows for easier trade and business opportunities in Western countries.

- Certain flag registries, such as Panama, are much less strict about employee protections, enabling long voyages with continuous operations, without labor law concerns.

Prolonged voyages worldwide are associated with ecological damage, but also human rights violations. Let’s take a look at the Pacific Ocean again, as it offers interesting data.

Of the +2,000 Chinese fishing vessels that operate in the Pacific Ocean, at least 38% were not observed by Windward in any port for at least six months, and 23% of them were not seen in any port over the past year. Stanford’s Center for Ocean Solutions has addressed these types of long voyages and the accompanying abuse:

“Fishing vessels engaged in IUU fishing often engage in labor abuses including, exploitation, forced labor, debt bondage, human trafficking, and modern slavery. Crews can be trapped at sea for months or years at a time, working in grueling conditions and sometimes facing wanton brutality. Wages are withheld or simply never paid. While there are not reliable global statistics on the extent of labor abuse in the seafood sector, civil society organizations, researchers and investigative journalists are increasingly demonstrating that abuse is more widespread than previously thought.”

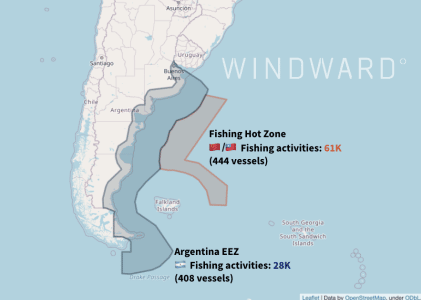

In figure 9 above, the gray area represents the official EEZ and the orange outline shows a hot zone in international waters identified by Windward’s platform.

While 408 Argentinian-flagged vessels engaged in only +28,000 activities within the Argentinian EEZ, 444 Chinese and Taiwanese-flagged vessels participated in +60,000 fishing activities – all occurring in the hot zones flagged by Windward.

This kind of activity exposes Argentina to potential economic (and other types of) harm:

“‘The vessels that disappear along the edge of the national waters of Argentina could be pillaging its waters illegally,’ said Oceana’s deputy vice president of U.S. campaigns, Beth Lowell… ‘IUU fishing is wreaking havoc on our oceans, coastal communities, and people who depend on the oceans for their livelihoods.’…As part of (its) analysis (from January 1, 2018-April 25, 2021), Oceana documented more than 6,000 gap events, instances where AIS transmissions are not broadcast for more than 24 hours, which can indicate where vessels potentially disable their public tracking devices. These vessels were invisible for more than 600,000 total hours, hiding fishing vessel locations and masking potentially illegal behavior, such as crossing into Argentina’s national waters to fish…Interactions between the Argentine Coast Guard and suspected illegal fishing vessels have escalated to violence, with some deeming the conflict ‘a literal war.’”

In line with our supporting hubs analysis, Windward’s data showed that most of these Chinese and Taiwanese vessels use a few of our identified supporting hubs – Montevideo, Uruguay (10% as the origin port, 39% as the destination port) for Chinese vessels and Stanley Harbor, Falkland Islands (4% as the origin port, 4% as the destination port) for Taiwanese vessels – to continue their operations and discharge their illegal catch for sales.